Getting Started

File Format

Tutorial

Your First Hurl File

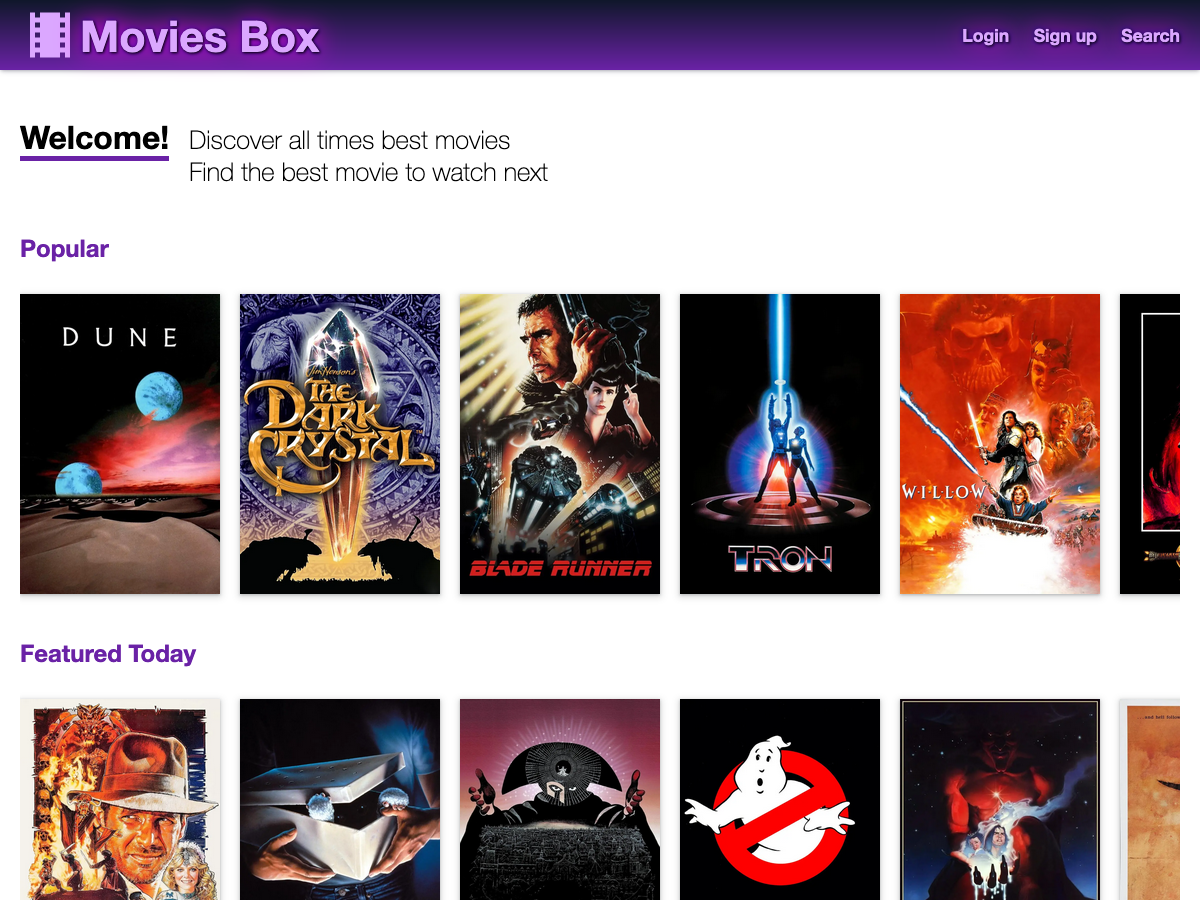

Throughout this tutorial, we’ll walk through the creation of multiple Hurl files to test a basic web application about movies called Movies Box. The source code of the project is at https://github.com/jcamiel/hurl-express-tutorial. We’ll show how to test this site locally, and how to automate these integration tests in a CI/CD chain like GitHub Action and GitLab CI/CD.

Our Movies Box website consists of:

- a website that lets people make list of favorite movies

- a set of REST APIs to search movies, add, remove favorites

With Hurl, we’re going to add tests for the website and the APIs.

Prerequisites

We’ll assume you have Hurl installed already. You can test it by running the following command in a shell prompt (indicated by the $ prefix):

$ hurl --version

If Hurl is already installed, you should see the version of Hurl. If it isn’t, you can check Installation to see how to install Hurl.

Next, we’re going to install our movies application locally, in order to test it.

Hurl being really language agnostic, you can use it to validate any type of application: in this tutorial, our quiz application is built with Express, a Node.js framework, but this could as well be a Spring Boot or a Flask app.

Our movies application can be launched locally either:

- using a Docker image

- using Node

If you want to use the Docker image, you must have Docker installed locally. If it is the case, just run in a shell:

$ docker pull ghcr.io/jcamiel/hurl-express-tutorial:latest

$ docker run --name movies --rm --detach --publish 3000:3000 ghcr.io/jcamiel/hurl-express-tutorial:latest

And check that the container is running with:

$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

4002ce42e507 ghcr.io/jcamiel/hurl-express-tutorial:latest "node dist/bin/www.js" 3 seconds ago Up 2 seconds 0.0.0.0:3000->3000/tcp, :::3000->3000/tcp movies

If you want to launch the Node application, you must have Node installed locally.

$ git clone https://github.com/jcamiel/hurl-express-tutorial.git && cd hurl-express-tutorial

$ npm install

$ npm start

Either you’re using the Docker images or the Node app, you can open a browser and test the website by typing the URL http://localhost:3000:

Play a little with the site. You can see details of each movie, search for movies (try “1982”), login to add favorites

(use username fab and password 12345678).

A Basic Test

Next, we’re going to write our first test.

- Open a text editor and create a file named

basic.hurl. In this file, just type the following text and save:

GET http://localhost:3000

This is your first Hurl file, and probably one of the simplest. It consists of only one entry.

An entry has a mandatory request specification: in this case, we want to perform a

GETHTTP request on the endpoint http://localhost:3000. A request can be optionally followed by a response description, to add asserts on the HTTP response. For the moment, we don’t have any response description.

- In a shell, execute

hurlwithbasic.hurlas argument:

$ hurl basic.hurl

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<title>Movies Box</title>

<link rel="icon" type="image/png" href="/img/favicon.png" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/css/style.css" />

</head>

<body>

....

</html>

If the Movies Box website is running, you should see the content of the HTML file at http://localhost:3000.

If the website is not running, you’ll see an error:

$ hurl basic.hurl

error: HTTP connection

--> basic.hurl:1:5

|

1 | GET http://localhost:3000

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ (7) Failed to connect to localhost port 3000 after 6 ms: Couldn't connect to server

|

As there is no response description, this basic test only checks that an HTTP server is running at

http://localhost:3000 and responds with something. If the server had a problem on this endpoint, and had responded

with a 500 Internal Server Error, Hurl would have just executed successfully the HTTP request,

without checking the actual HTTP response.

As this test is not sufficient to ensure that our server is alive and running, we’re going to add some asserts on

the response and, at least, check that the HTTP response status code is 200 OK.

- Open

basic.hurland modify it to test the status code response:

GET http://localhost:3000

HTTP 200

- Execute

basic.hurl:

$ hurl basic.hurl

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<title>Movies Box</title>

<link rel="icon" type="image/png" href="/img/favicon.png" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/css/style.css" />

</head>

<body>

....

</html>

There is no modification to the output of Hurl, the content of the HTTP request is outputted to the terminal. But, now,

we check that our server is responding with a 200 OK.

By default, Hurl behaves like curl and outputs the HTTP response. This is useful when you want to get data from a server, and you need to perform additional steps (like login, confirmation etc...) before being able to call your last request.

In our case, we want to add tests to our project, so we can use --test command line option to have an adapted

test output:

- Execute

basic.hurlin test mode:

$ hurl --test basic.hurl

basic.hurl: Success (1 request(s) in 24 ms)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Executed files: 1

Executed requests: 1 (41.7/s)

Succeeded files: 1 (100.0%)

Failed files: 0 (0.0%)

Duration: 24 ms

- Modify

basic.hurlto test a different HTTP response status code:

GET http://localhost:3000

HTTP 500

- Save and execute it:

$ hurl --test basic.hurl

error: Assert status code

--> basic.hurl:2:6

|

| GET http://localhost:3000

2 | HTTP 500

| ^^^ actual value is <200>

|

basic.hurl: Failure (1 request(s) in 10 ms)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Executed files: 1

Executed requests: 1 (83.3/s)

Succeeded files: 0 (0.0%)

Failed files: 1 (100.0%)

Duration: 12 ms

- Revert your changes and finally add a comment at the beginning of the file:

# Our first Hurl file, just checking

# that our server is up and running.

GET http://localhost:3000

HTTP 200

Recap

That’s it, this is your first Hurl file!

This is really a basic test, but it shows how powerful Hurl’s simple file format is. We’re going to see in the next section how to improve our tests while keeping it really simple.